The anabolic window: A stressful race against time where after a workout, your prime opportunity to consume nutrients hinges on this 30 min-1hr timeframe. Some say this timeframe is even more effective for optimal muscle growth than your total daily caloric intake and if this window of opportunity is missed, then your entire workout is a waste. In theory, this sounds fairly intuitive. You just spent about an hour tearing your muscles down and heightening your muscle protein synthesis. Naturally, it seems the intake of nutrients would be guided to building muscle and restoring your glycogen. But how accurate is this statement? Does the anabolic window really exist and if it does, has it simply been blown way out of proportion by the fitness and the supplement industry? What research has been done and how conclusive has science been to support this topic or dispel this myth?

Those who support the concept of the Anabolic Window suggest that you should consume protein and fast-digesting carbs right after your workout. The case for protein is pretty clear. Since amino acids are the building blocks of muscle, you’d want plenty of protein in your system to aid in repair and growth. Fast digesting carbs are purported to serve dual purposes. First, they restore your glycogen levels. In case you aren’t aware, glycogen is just the stored carbohydrate in your muscles used as fuel during workouts.

Replenishing this storage gives you strength for your next workout and gives your muscles a “fuller” look. Secondly, it’s said that fast-digesting carbs spike your insulin levels way up. Although insulin typically draws a negative connotation for storing body fat, it also aids in transporting nutrients to muscle cells faster. And that’s basically it—sounds too good to be a myth right? In fact, like a lot of myths that circulate the gym these days, there is a grain of truth in them and the principle from which they originally stemmed is fairly scientifically sound, if not intuitive. But when information is constantly shared back and forth, it’s inevitable for some things to get lost in translation.

So how did this myth really get started and how has it perpetuated all this time? Well, based on my research, it seems people have been aware of the concept for a while. But it was probably popularized in 2004 by Dr. Robert Portman and John Ivy in their book “Nutrient Timing: The Future of Sports Nutrition.” The principle message was that an athlete could drastically augment size, strength and recovery after a workout if he/she consumed the proper ratio of nutrients in the appropriate time frame. Doing otherwise would yield less than stellar results and significant delays could even lead to adverse effects.

The problem with this and subsequent studies are the limitations in the body of evidence that make the anabolic window a more inconclusive topic rather than downright false. For instance, almost all studies that were conducted involved endurance athletes on recumbent bikes rather than a resistance-training regimen. Some studies involved a group that consisted of untrained or elderly individuals while the short-term effects of supplementation limited other studies. Further still, the control group in comparison to the experimental group consumed less protein throughout the day. These shortcomings make it especially difficult when gauging the effect of nutrient timing in experienced strength-trained athletes. With that said, let’s examine some of these assertions.

- Increasing muscle mass: The goal for increasing muscle mass is often the first reason people believe they need to immediately consume a meal after their workout. I’ve been guilty of this, but I speculate that sometimes what people believe is the anabolic window is simply the time their pump lasts after a workout. I can’t begin to tell you how many times I felt as if I had to chug a protein shake before my pump would disappear, which as we all know, never lasts. So in a way, this idea of equating the anabolic window with your pump is partially psychological. But it turns out research has shown that immediate post-workout protein and carb intake is not nearly as necessary as maintaining adequate protein intake over a 24-hr period. In a 2013 study done by Aragon and Schoenfeld, it was demonstrated that a composite group consisting of young, elderly, fit and obese subjects, did not depend on an increased need for protein after a workout.

- Preventing muscle breakdown: The second reason is the desire to prevent muscle breakdown. The belief here is that in order to prevent protein breakdown, you need to immediately transport protein straight back to your muscle tissues by spiking your insulin. This is why you’ll often hear people suggest consuming dextrose or simple sugars. However, studies indicate that the breakdown of protein in muscle tissue is only slightly raised immediately following an intense workout. This makes the consumption of a protein shake marginally beneficial. There is a caveat: Those who engage in fasted workouts have demonstrated evidence that muscle protein breakdown is considerably heightened, making a post-workout meal far more important. By fasted workout, I mean at least 8-10 hrs before your last meal. The best example of this is going to the gym in the morning without consuming breakfast. However, since fasted workouts have become increasingly more popular due to intermittent fasting, this can be anywhere in your day depending on your eating patterns.

- And the third reason is replenishing your glycogen storage. Glycogen is one of your primary energy sources and after a workout, these carbs are typically depleted. If your goal is to build muscle and get stronger you’re going to need to replenish this energy storage. However, in an article by Martin and Carey, it was demonstrated that muscle glycogen repletion was about the same 24 hours later, whether carbs were consumed immediately or several hours later a workout. Again, the only caveat, in this case, would be for competitive athletes who trained multiple times a day, such as a swimmer. Unless you plan on working out again after a few hours, there simply is no need to replenish immediately. Your main goal would simply be to make sure you’re consuming adequate amounts of carbs throughout the day.

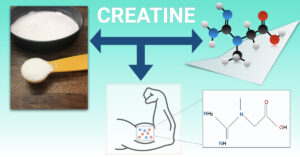

So, does this mean that nutrient timing unnecessary? Not exactly. There have been some articles written about the benefits of pre-workout meals. By pre-workout, I’m talking about ingesting a meal 1-3hrs before training. In a 10-week study done by Cribbs and Hayes, a study was designed so that participants in one group would consume a supplement of protein, carbohydrates, and creatine immediately before and after a workout versus a group that would consume the same supplement several hours before and after a workout. The first group “demonstrated a greater increase in lean body mass and 1RM strength in two of three assessments.”

On the other hand, in a recent study done by Schoenfeld, it was revealed that even just 25g of protein before resistance style training was sufficient for muscle growth and that 20g of protein ingested before a workout increased amino acid uptake by the muscles during and up to three hours after a training session. Partially, this is simply because digestion is a long and complex process. Even fast-digesting food sources will still take onwards up to 45 minutes to find its way through your digestive tract before being shuttled to your muscle cells. This suggests that if you’ve eaten a pre-workout meal, you can rest easy knowing that there are still nutrients circulating by the time you’ve completed your last set.

Finally, it is important to note that simply lifting weights spikes levels of muscle protein synthesis and as long as your rate of synthesis is greater than your rate of protein breakdown, you will build muscle. To be more specific, a study done by Shriners Burns Institute showed that after resistance training, muscle protein synthesis was heightened 112% percent after 3 hours, 65% after 24 hours and 34% after 48 hours. Muscle fractional breakdown rate was also heightened 31% after 3 hours, 18% after 24 hours and returned to normal after 48 hours. It was concluded that exercise “resulted in an increase in muscle net protein balance that persisted for up to 48 h after training and was unrelated to the type of muscle contraction performed.” This shows there is at minimum a 3-hour period after a workout session where your body builds muscle faster than it breaks it down.

As you can see, despite claims that immediate nutrient consumption is required post-workout to maximize muscular gains, the anabolic window is far from a conclusive argument. In the study done by Schoenfeld, it was ultimately concluded that there is a lack of definitive research to support the claim of a narrow window of opportunity to maximize strength or hypertrophic adaptation. Research shows that consuming protein and carbs after training will lead to positive results but whether it is immediately after or several hours later, a significant difference has not been demonstrated.

Thus, studies side more with that fact the anabolic window is a less useful measure of growing muscle than calorie and nutrient tracking throughout the day. The fact is, if you’ve developed a regimen when it comes to consuming a meal post-workout, continue doing so. It certainly can’t hurt. But unless you are training fasted, don’t feel that there’s automatically a countdown you have to beat after you finish your last rep. A lot of times, myths in the gym are rooted in some scientific basis but often devolve into non-facts. The supplement industry is partially to blame.

In order to better sell their products, naturally, it would be in their interest to advertise these concepts. If they can incentivize a way for consumers to purchase products based on a sense of urgency when it comes to muscle recovery…well, you can see how something like the anabolic window would be an excellent marketing scheme. Now I’m not saying that I don’t take supplements—I definitely do. But I certainly am not persuaded to spend 900 dollars a month on them just because of a new myth circulates the gym. And those are my conclusions.

Summary

- Don’t confuse your pump with nutrient timing. Your pump will never last and is not synonymous with the anabolic window. It’s all psychological.

- Increasing muscle mass is far more efficient when you are properly tracking your macros THROUGHOUT the day, not just after your workout.

- Protein breakdown is only SLIGHTLY raised for a brief period of time. Unless you are training fasted, you won’t experience breakdown.

- Glycogen storage can be replenished immediately or several hours later. Unless you are an athlete or train multiple times a day, you don’t have to worry about immediate repletion.

- Net muscle protein synthesis is heightened for a minimum of 3 hours after a workout.

- Be cautious about how supplement industries market their product based on the claim of vague scientific studies.

- The length of your feeding window is a lot more flexible than you might think. Nutrient timing should be planned based on your personal schedule.